Weaving a Golden Legacy: The Revival of Telepuk in Terengganu

At the heart of Kampung Budaya Terengganu stands Rumah Tele, bearing silent witness to the passage of time. Built in 1888, the house was moved not once, but twice — first from its original Maziah Palace location to Padang Negara, Kuala Ibai, and later, in 1987, to its present space within the state museum grounds.

Just as this woodworking marvel — also known as Rumah Bujang Berserambi or Istana Tengku Nik — was preserved and repositioned to endure, so too is the heritage textile Telepuk. Once at risk of fading into the footnotes of history, it lives on through the hands of those restoring its golden imprint on the nation’s cultural fabric.

Inside Rumah Tele, artisan Mohd Azwarin B Ahmed applies gold leaf onto fabric, his touch delicate, deliberate, and defiant of time. This is Telepuk, one of the oldest textile crafts in Malaysia.

Opulent and grand, it was once reserved for nobility and seen on royal regalia such as baju sikap, coronation robes, samping, and headdress for weddings.

Uncovered from the Sands of Time

Telepuk is believed to have existed since the 17th or 18th century, though some trace it to Kesultanan Melayu Melaka.

References to this textile can be found in Syair Siti Zubaidah Perang Chik, where it is called perada. Other ancient literature suggests the word “Telepuk” was used to describe a type of lotus, the Nymphaea stellata. Experts differ on whether this was a metonym for the floral motif stamps, or a metaphor for the shimmering effect of the gold foil — glistening like lotuses on a sunlit lake.

“It tells a beautiful story, one of a global Malaya. It is an art form that other countries also practiced, for example varak in India,” Yayasan Hasanah’s Head of Arts and Public Spaces Nini Marini says. In Indonesia it is known as kain perada/preda and in Korea it is gyumbak.

In The Malays: A Cultural History, Richard Winstedt wrote:

“Patani, Pahang and Selangor produce cloths (kain telepuk) gilded by a technique practised also in the Punjab. Cotton with a small pattern on a dark green or dark blue ground is polished (with cowry shells), stamped with carved wooden blocks that have been smeared with gum, and then covered with gold leaf that adheres to the gummy pattern.”

That excerpt describes the very process that Azwarin demonstrates to museum visitors daily.

“99 percent have never seen or heard about it,” he says, confessing he was initially skeptical if anyone would be keen. “There’s a Telepuk display in the museum complex, so visitors often come in already curious and excited to see how it’s made,” he adds, smiling.

These moments often spark conversations — which Nini believes are meaningful ways to build awareness of the art’s depth.

It tells a beautiful story, one of a global Malaya. It is an art form that other countries also practiced, for example varak in India.”

Nini Marini

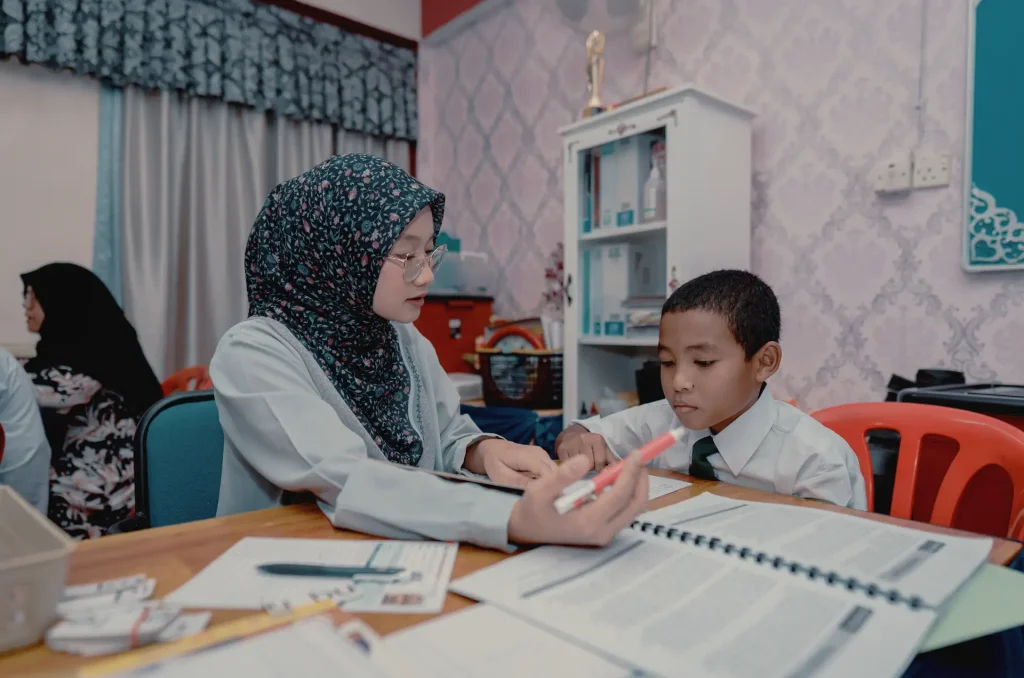

Under the Tutelage of a Master

Azwarin’s first glimpse into the world of Telepuk was in 2004 when he chose it as the subject of his final year assignment. The lack of information was immediately apparent.

“I managed to complete my assignment but my heart was not satisfied; I wanted to learn more.”

It wasn’t until 2017 that he found a workshop in Selangor. Here, he learned the craft from the late Adiguru Norhaiza bin Noordin marking the start of a cherished bond between the two Terengganu-borns.

Azwarin describes Abe Jah, as he is fondly called, as being generous with his wealth of knowledge, open to views even from those younger and less experienced, and passionate about preserving authenticity. He recalls them joking like friends, and many conversations about the mysteries of this heritage art and how to produce the best Telepuk.

Abe Jah once said to him: “Today you’re learning because of interest but one day it will become your responsibility.” Azwarin may not have fully comprehended the gravity of that message then but these words ring differently since his passing last December.

Hasanah’s Telepuk revival journey with Abe Jah began in 2019, supporting research and workshops in collaboration with project partner Lamar Dollar with the late master craftsman at the forefront.

Supported by Yayasan Hasanah and the Ministry of Finance, the recent launch language book titled Telepuk: Forgotten Flowers of Gold and a series of public activations have brought this heritage art once only known to royals, even closer to the rakyat.

Getting to Know the Forgotten Flowers

There are four intricate processes to Telepuk-making: weaving fine silk, labor-intensive calendering using a siput gerus shell, carving detailed wooden stamps, and finally gilding the cloth with gold leaf.

Motifs like daun inai, pucuk rebung, bunga cengkih and bunga kenanga celebrate our country’s rich flora — visually striking, and symbolic of royal lineage, says Nini.

There are also rules surrounding their application. Azwarin tells us that the iconic pucuk rebung design can only be used at the head portion of the cloth, while the shape of the bamboo shoot indicates the state it hails from.

Cost is a challenge artisans face. “Sometimes people want to see samples but all my work is commissioned and now with the owners,” says Azwarin who is saving up to make more display pieces.

Even so, he always leaps at any opportunity to introduce Telepuk to more people. “Even if the payment is small, I will still go to raise awareness.”

On hopes for the future, Nini cites “artisans being acknowledged for their artistry and paid well for their craft.” She hopes to see this heritage textile gracing the walls of homes, if not worn, worldwide.

In its Golden Era

Once the domain of nobility, Telepuk is now returning to national appreciation.

Its exclusivity endures, not through restriction, but through reverence. From the use of 24-karat gold leaves to the ritual of wukuk kain — where garments are perfumed with the smoke of pandan leaves, flowers and sugarcane — every step is steeped in ceremony and splendour.

It is a grandeur not newly made, but long remembered — as this passage from the Hikayat Misa Melayu so vividly reveals:

“Adapun akan berjaga-jaga itu pun sampailah empat puluh hari empat puluh malam. Maka Balai Pancha Persada itu pun sudahlah diperbuat orang, maka terlalulah indah perbuatannya, kemuncak tungkubnya, ditatah dengan emas kerincing dan sulur bayungnya daripada perak, ditatah dengan perda terbang, tiangnya gadingan disendi dengan tanduk diukir dicat dengan sadalinggam, …”

Breaking Tradition: Pasar Besar Siti Khadijah’s Digital Revolution

Weaving a Golden Legacy: The Revival of Telepuk in Terengganu

Mental Health Warriors of PPR Batu Muda

Everyday Heroes: The Malaysians Who Show Up in Times of Crisis

Breaking Taboos: Teachers Lead Kelantan’s Sexuality Education Revolution

Keeping A Traditional Dance Alive: An Homage to Kuda Pacu

Darkness to Light: Water Access and Solar Power Transforms Perak’s Village

Abbernaa: From Classical Dance to Policy Research

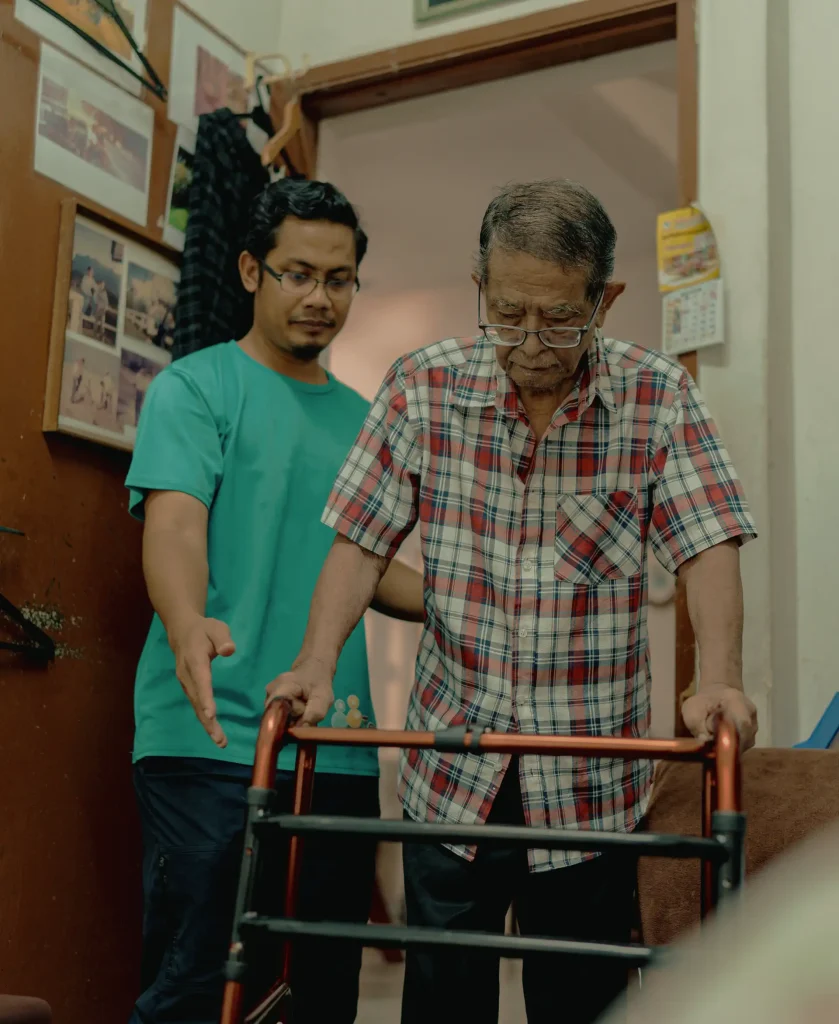

JomBaca: Driving Learning Recovery, Reigniting Dreams for Our Children

Teman: Fighting Loneliness in an Aging Malaysia

Net Positive: Fishers Protecting Marine Mammals

Vanilla Impact: Uncle Alfred’s Mission in Reviving Spice

The Mission to Save our Bornean Sun Bear