Net Positive: Fishers Protecting Marine Mammals

At a workshop conducted by MareCet Marine Mammal Research & Conservation (MareCet), participants gather around a dolphin, beached on a blue tarpaulin.

It is not real — just an inflatable stand-in, used to teach local fishers and members of the public what to do in the event of a stranding. Around it, hands learn to lift, cradle, and release with care. The mood is light, curious. Jokes are made. Photos are taken.

But the reality that this training prepares for is anything but gentle.

When a marine mammal caught in a net is not discovered in time, panic sets in. It thrashes, rolls, and tightens the mesh around its body, suffocating it. Fishers are sometimes able to release them albeit wounded but often it is too late — and the cost is borne by both animal and human: a life lost, a net ruined, a day’s catch gone.

Globally, it is estimated over 300,000 cetaceans are killed as by-catch each year — a trend mirrored in Southeast Asia. While the actual rate of strandings in Malaysia is unknown, reports have increased in recent years, often linked to by-catch incidents.

In Kuala Sepetang (also known as Port Weld), complexities of coexistence are becoming harder to ignore. At this coastal fishing village where river meets sea, daily life is shaped by tide and catch.

Bordering its waters is the Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve, a century-old ecosystem often cited as a global model for sustainable forestry. Spanning over 40,000 hectares, it supports rich fisheries and provides vital habitat for marine mammals such as the Irrawaddy dolphins, Indo-Pacific humpbacks and finless porpoises.

Dolphins have become a local draw, their silhouettes surfacing briefly as tourists reach for cameras. But behind the postcard moment lies a quieter truth: these same waters pose hidden risks, where fishing nets meant for catch can turn into traps.

Navigating the Delicate Balance Between Life and Livelihood

MareCet has been tirelessly working with fishers to reduce incidents of by-catch and depredation.

“Matang Dolphin project started in 2013,” explains Dr. Vivian Kuit, MareCet council member and scientific officer, “and from our research we found that by-catch or accidental entanglements is one of the biggest threats to cetaceans here.”

Environment Grant Executive Nadiah Amirah, explains how this initiative aligns with Hasanah’s broader sustainability goal ensuring a balance between environmental conservation and livelihood of local communities.

“Rather than restricting fishing activities, we believe in empowering fishers by involving them in conservation efforts. Their participation as citizen scientists allows them to better understand the importance of marine biodiversity and become key contributors to sustainable fishing practices.”

MareCet’s use of acoustic pingers — devices that emit high-frequency sounds to deter dolphins — aims to protect vulnerable species like the Irrawaddy dolphin (classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List), the Indo-Pacific humpback, and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise, all protected under Malaysia’s Fisheries Act 1985.

216 pingers have been distributed thus far and currently 34 fishers participate in this by-catch mitigation project.

Getting fisher buy-in, however, was no easy task as many were concerned that the pingers would affect their catch.

“Few daring fishers got the ball rolling. They also contributed data to us by filling up a form declaring dolphin sightings, type of fish caught, as well as instances of by-catch or depredation.”

One pioneering fisher, Yeoh Teik Chin, saw the method’s effectiveness firsthand — and began advocating for it among his peers. He says the pingers have kept dolphins away from his nets.

MareCet also teaches them how to properly attach pingers to nets as well as maintenance such as checking battery levels and replacing when needed.

Few daring fishers got the ball rolling. They also contributed data to us by filling up a form declaring dolphin sightings, type of fish caught, as well as instances of by-catch or depredation.”

Dr. Vivian Kuit

Cultivating Public Awareness

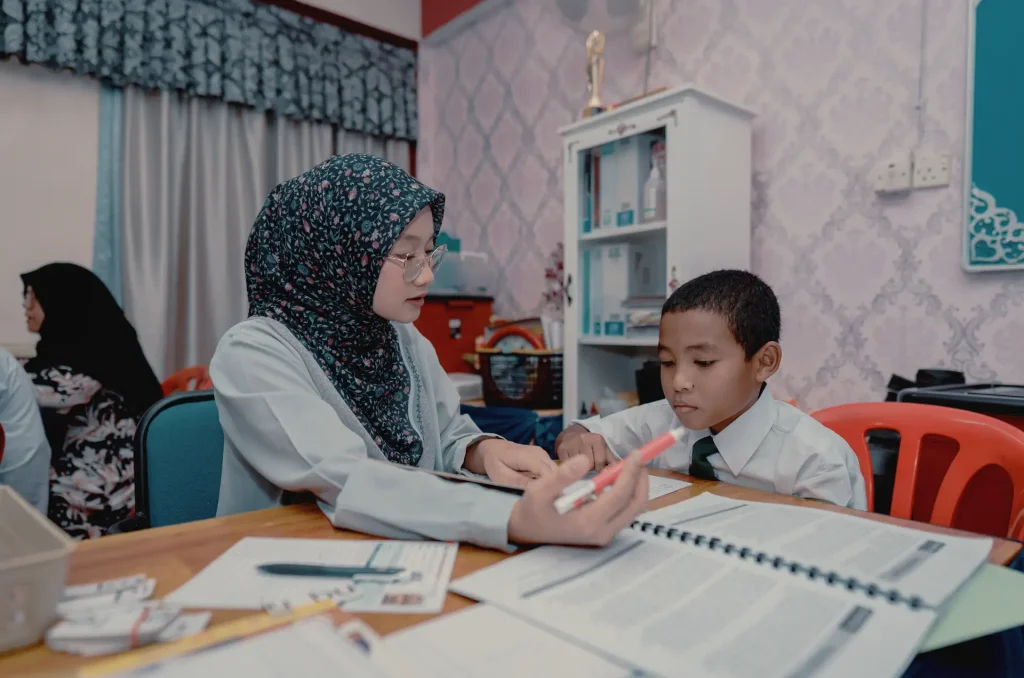

Another equally important arm of the project is the series of stranding and safe release workshops, designed to equip both fishers and the public with lifesaving knowledge. So far, three workshops have been held for fishers and one for the public, drawing 179 and 51 attendees respectively. Education is vital because in the event of a stranding, every minute can mean the difference between life and death.

Dr. Vivian’s hope for marine conservation in Malaysia is clear: “That we are able to expand the use of pingers to other parts of the country — and perhaps even regionally.”

While progress has been made, much more remains to be done. Long-term conservation success will require deeper collaboration — between technical experts like MareCet, local communities, government, and the private sector. Hasanah remains committed to fostering these partnerships, helping ensure that Malaysia’s coastal ecosystems can thrive for generations to come.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Kuala Sepetang. It was here that Malaysia’s first railway line once linked the tin-rich hills of Taiping to the open coast. Today, it stands at another kind of crossroads: between tradition and transformation, between livelihood and care — between what has always been done and what must now begin.

Breaking Tradition: Pasar Besar Siti Khadijah’s Digital Revolution

Weaving a Golden Legacy: The Revival of Telepuk in Terengganu

Mental Health Warriors of PPR Batu Muda

Everyday Heroes: The Malaysians Who Show Up in Times of Crisis

Breaking Taboos: Teachers Lead Kelantan’s Sexuality Education Revolution

Keeping A Traditional Dance Alive: An Homage to Kuda Pacu

Darkness to Light: Water Access and Solar Power Transforms Perak’s Village

Abbernaa: From Classical Dance to Policy Research

JomBaca: Driving Learning Recovery, Reigniting Dreams for Our Children

Teman: Fighting Loneliness in an Aging Malaysia

Net Positive: Fishers Protecting Marine Mammals

Vanilla Impact: Uncle Alfred’s Mission in Reviving Spice

The Mission to Save our Bornean Sun Bear